In a digital age, how can we reconnect values, principles and rules?

As we write this there is an ongoing conversation about the regulation of Facebook and the regulation of big tech in general. We see a problem with the frame of the conversation because we believe ON PRINCIPLE they shouldn’t exist as in no-one entity should have that much power and control over the global population’s identities, “their” data and the conversion we have. So any frame that accepts BIG TECH as acceptable won’t create rules that actually move towards the principle of ending the current hegemony but rather just seek to regulate it as is.

With this piece, we are seeking to look at how principles change when the underlying fabric of what is possible changes? The entire privacy framework we have today is based on early 1970’s reports written in the United States to address concerns over mass state databases that were proposed in the mid-late 1960’s and the growing data broker industry that was sending people catalogues out of the blue. It doesn’t take account for the world we live in now where “everyone” has a little computer in their pocket.

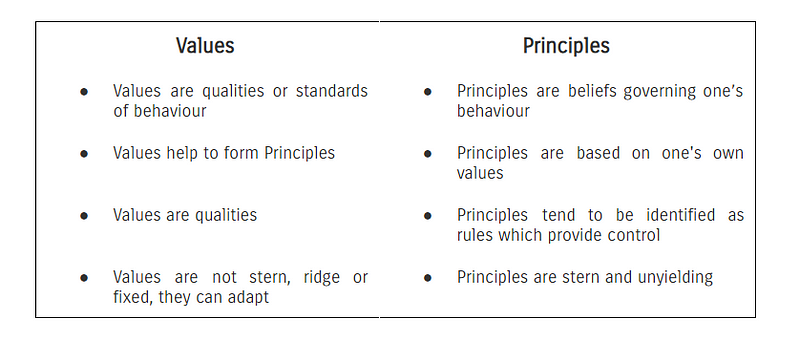

So let’s get to the question at hand “Why does it matter that we connect values, principles and rules?” The connection is not clear because we have created so many words and variance in languages that there is significant confusion. We are often confused in ourselves to what we mean, we are very inconsistent in how we apply our understanding, often to provide a benefit to ourselves or justify our belief. To unpack the relationship we need to look at definitions, but we have to accept that even definitions are inconsistent. Our conformational bias is going to fight us, as we want to believe what we already know, rather than expand our thinking.

Are we imagining principles or values?

Worth noting our principles are defined by our values. Much like ethics (group beliefs) and morals (personal beliefs) and how in a complex adaptive system my morals affect the group’s ethics and a group’s ethics changes my morals. Situational awareness and experience play a significant part in what you believe right now, and what the group or society believes.

Values can be adaptable by context whereas principles are fixed for a period, withstanding the test of time. When setting up a framework where we are setting our principles implies that we are saying that we don’t want them to change every day, week, month, year, that they are good and stable for a generation but we can adapt/ revise/ adjust principles based on learning. Fundamentally principles are based on values which do change, so there are ebbs and flows of conflict between them, this means we frame principles and often refuse to see that they are not future proof forever. Indeed the further a principle is away from the time it was created, the less it will have in common with values.

Are we confusing principles and rules?

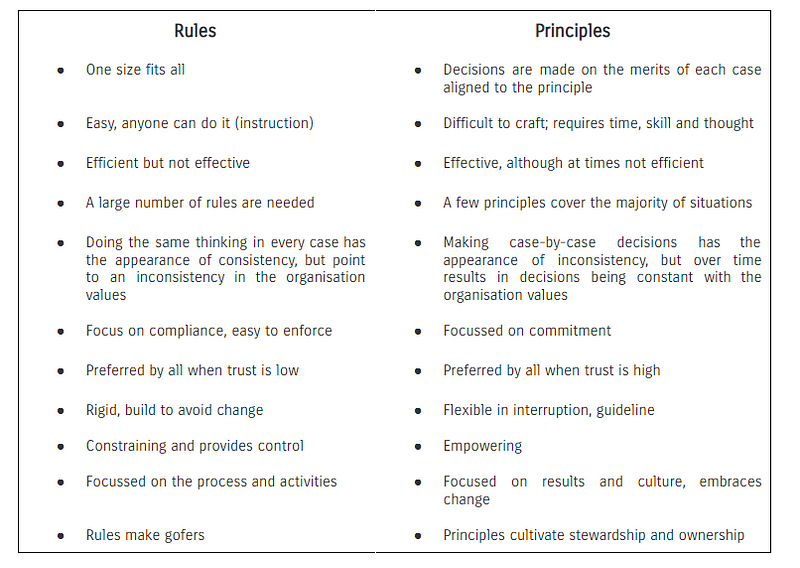

Considering characteristics, conceptually principles are abstract and universal whereas a rule is specific and particular. Principles cope with exceptions, rules need another rule. Principles provide the power of thought and decision making, rules prevent thought and discretion. Principles need knowledge and experience to deliver outcomes, rules don’t. Principles cope with risk, conflict and abstraction; conflict is not possible for a rule, it is this rule or a rule is needed.

We love rules-of-thumb, as such rules and heuristics provide time-saving frameworks which mean we don’t have to think. Not having to think saves energy for things we like to do. Take away the little ways you have that creates a stable place for yourself and you end up exhausted. Travel to a new place and you don’t know where the simple amenities of life are, COVID19 took away the structure of our lives which created exhaustion until we found a new routine. However, we often confuse “our heuristics”, the way I do something, or “my rules” as a principle. This diet rule is a principle for losing weight. We should accept that we purposely interchange rules, values and principles to provide assurance and bias to the philosophy, theory, thesis or point we are trying to gain acceptance of.

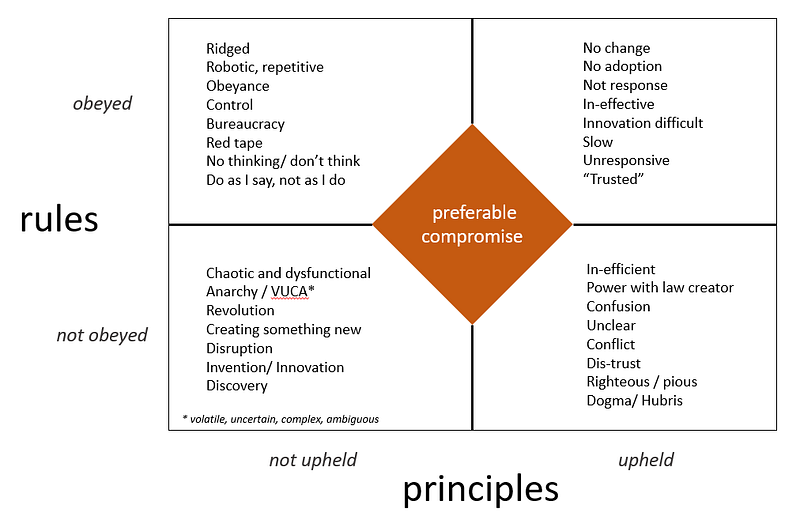

In companies and for a social policy we set rules and principles into matrices as below. Asking is it better to break rules or comply, is better to uphold principle or challenge them.

A review round the four quadrants highlights that there is no favourable sector and indeed as a society who wants to get improve, we continually travel through all of them. Companies and executives often feel that upholding principles and obeyed rules (top right) creates the best culture, but also ask the organisation to be adaptive, agile and innovative.

Given that principles are based on values, the leadership team will be instrumental into how upheld the principles are. Whereas the companies level of documentation for processes, procedures and rules will define what is to be obeyed, the culture of the top team will determine if they are to be obeyed or not.

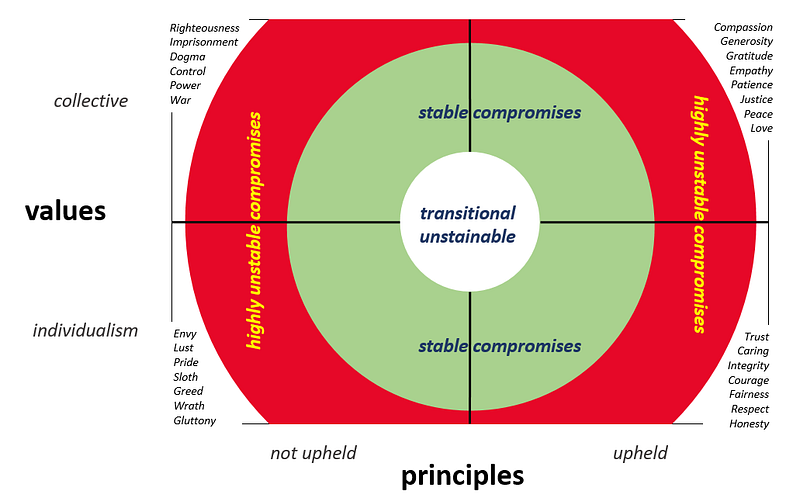

The matrix below thinks about the combinations of values and principles. Where values are either mine as an individual or we as a collective society.

The fundamental issue with the two representations (rules or values and principles) is that they cannot highlight the dynamic nature of the relationship between them. By example, our collective values help normalise an individuals bias and that collective values informs and refine principles. Indeed as principles become extreme and too restrictive say as our collective values become too godly, our collective values opt to no-longer uphold them. When our individualism leads to the falling apart of society we raise the bar to create better virtues as it makes us more content, loved and at peace.

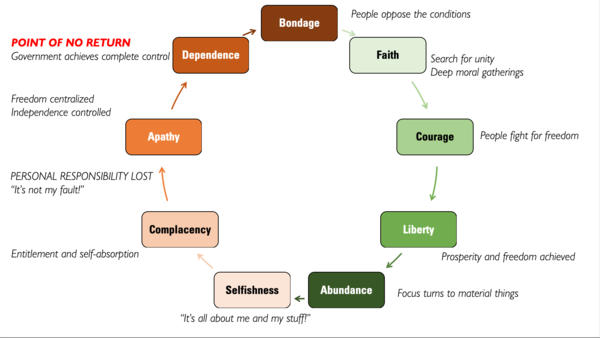

Movement within the “stable compromise” domain has been explored many times but the Tytler cycle of history expands it very well.

In summary, a rules-based approach prescribes or describes in detail a set of rules and how to behave based on known and agreed principles. Whereas a principle-based approach develops principles which set the limits that enable controls, measures, procedures on how to achieve that outcome is left for each organisation to determine.

Risk frameworks help us to connect principles and rules

Having explored that a rules-based approach prescribes in detail the rules, methods, procedures, processes and tasks on how to behave and act, whereas a principle-based approach to creating outcomes crafts principles that frame boundaries, leaving the individual or organisation to determine its own interruption.

- In a linear system, we would agree on principles which would bound the rules.

- In a non-linear system, we would agree on the principles, which would bound the rules and as we learn from the rules we would refine the principles.

- In a complex adaptive system, we are changing principles, as our values change because of the rules which are continually be modified to cope with the response to the rules.

This post is titled “In a digital age, how can we reconnect values, principles and rules?” and the obvious reason is that rules change, values, which change principles that means our rules need to be updated. However, this process of learning and adoption depends on understanding the connection which offers closed-loop feedback. An effective connection is our risk frameworks.

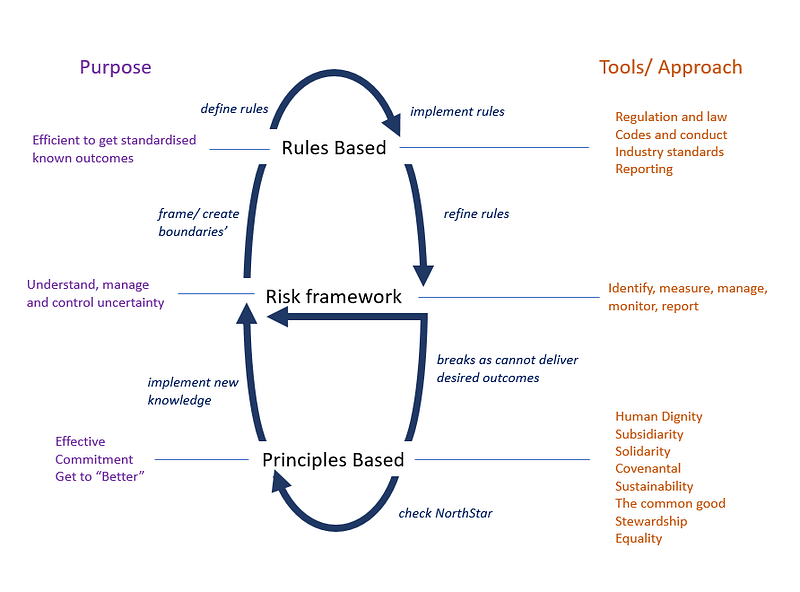

The diagram below places rules and principles at two extremes. As already explored we move from principles to rules but rarely go back to rethink our principles, principally because of the time. Rules should refine and improve in real-time, principles are generational. However to create and refine rules we use and apply a risk framework. The risk framework identifies risk and to help us manage it, we create rules that are capable of ensuring we get the right data/ information to be able to determine if we have control over risk. As humans, we are not experts in always forecasting the unimagined and so when we implement rules things break and clever minds think how to bend, break or avoid them. To that end we create more rules to manage exceptions. However, occasionally we need to check that our rules are aligned to our principles and indeed go back and check and refine our principles.

Starting from “Principles” these are anchored in ideas such as Human Dignity, Subsidiarity, Solidarity, Covenantal, Sustainability, The common good, Stewardship, Equality.

Once we decide that one or more of these should anchor our principles and form a north star, a direction to travel in and towards. The reason to agree on the Principle(s) is that collectively we agree on a commitment to get to a better place. We state our principles as an ambition, goal, target with allow us to understand, manage and control uncertainty using a risk framework. The risk framework frame or bounds the risk we are prepared to take. The risk framework enables us to define rules that get to our known outcomes. We implement the rules to create controls using regulation, code and standards. Our risk frameworks use tools to identify, measure, manage, monitor and report on the risk, the delta in risk and compliance with the rules. Whilst all is good we use the risk framework to create more rules and better framing and boundaries, creating better outcomes. However, when the desired outcomes are not being created we revert to the principles, check our north star and take our new knowledge to refine/ redefine the risk we are prepared to take.

Data and Identity Principles

Having established this framework, the idea is to apply this to the authors favourite topics of data and identity. We have an abundance of rules and regulations and as many opinions on what we are trying to achieve through identity and data ownership. We don’t appear to have an agreed risk framework at any level, individual, company, society, national or global. This is not a bill of rights, this is “what do we think is the north star for data and identity and on what principle they are built?” How do these principles help us agree on risks, and will our existing rules help or hinder us?

“what do we think is the north star for data and identity and on what principle they are built?” How do these principles help us agree on risks, and will our existing rules help or hinder us?

Our problems probably started a while back when information could travel faster than people (the telegraph rollout of 1850). This was a change in the fabric of values and principles. The person who was trusted was passed over and that person-to-person trust was no longer needed. Delays that allowed time for consideration gave way to immediacy; a shift in values and principles.

The question is how do our principles change when the underlying fabric of what is possible changes, the world we designed for was physical; it is now digital-first. Now we are becoming aware that the fabric has changed, where next? By example, Lexis is the legal system and database. With a case in mind, you use this tool to uncover previous judgments and specific cases to determine and inform your thinking. However, this database is built on humans and physical first. Any digital judgements in this database are still predicated on the old frameworks, what is its value when the very fabric of all those judgements changes. Do we use it to slow us down and prevent adoption? Time to unpack this

Physical-world first (framed as AD 00 to 2010)

Classic thinking (western capital civilisation philosophy) defined values and principles which have created policy, norms and rules. Today’s policy is governed by people and processes. We have history to provide visibility over time and can call on millennia of thought, thinking and wisdom. Depending on what is trending/ leading as a philosophy we create norms. In a physical and human first world, we have multi-starting positioning. We can start with a market, followed by norms, followed by doctrine/ architecture — creating law and regulations OR we can start with norms, followed by doctrine/ architecture, followed by market-creating law.

Without our common and accepted belief, our physical world would not work. Law, money, rights are not real, they are command and control schema with shared beliefs. Our created norms are based on our experience with the belief. We cope by managing our appetite to risk.

Digital world first (frame as AD 2020 — AD MMMCCX )

People-in-companies rather than people-in-government form the new norms as companies have the capital to include how to avoid the rules and regulations. The best companies are forming new rules to suit them. Companies have the users to mould the norms with the use of their data. Behaviour can be directed. Companies set their own rules. Doctrine/architecture creates the market, forming norms, and the law protects those who control the market. Policy can create rules but it has no idea how rules are implemented or governed as the companies make it complex and hide the data. There are few signs of visible “core” human values, indeed there are no shared and visible data principles. We are heading to the unknown and unimagined.

The companies automate, the decisions become automated, the machine defines the rules and changes the risk model. We are heading to the unknown and unimagined as we have no data principles.

By example. Our news and media have changed models. The editor crafted control to meet the demand of an audience were willing to pay to have orchestrated content that they liked. As advertising became important, content mirrored advertising preferences and editorial became the advertising and advertising the content. Digital created clicks that drove a new model to anything that drives clicks works. The fabric changed from physical to digital and in doing so we lost the principles and rules of the physical first world to a digital-first world that has not yet agreed on principles for data.

To our favourite topic: Data and Identity

Imagine looking at this framework of “principles, rules and risk” within the industry and sectors seeking to re-define, re-imagine and create ways for people to manage the digital representations of themselves with dignity. How would privacy and identity be presented?

Within data and identity, we have an abundance of rules and regulations and as many opinions on what we are trying to achieve. We don’t appear to have an agreed risk framework at any level, individual, company, society, national or global.

The stated GDPR principles are set out in Article 5:

- Lawfulness, fairness and transparency.

- Purpose limitation.

- Data minimisation.

- Accuracy.

- Storage limitation.

- Integrity and confidentiality (security)

- Accountability.

We know they are called “Principles” by the framing of the heading in Article 5, however, are these principles, values or rules? Further are these boundaries, stewardships or a bit of a mashup. By example to get round “Purpose Limitation,” terms and conditions become as wide as possible so that all and or any use is possible. Data minimisation is only possible if you know the data you want, which is rarely the case if you are a data platform. If a principle of The European Union is to ensure the free “movement/mobility” of people, goods, services and capital within the Union (the ‘four freedoms’), does data identity ideals and GDPR align?

Considering the issue with “the regulation of Facebook” or the “regulation of” Big Tech, in general, is that ON PRINCIPLE they shouldn’t exist, no one entity should have that much power and control over people’s identities and their data? So the framings that accept them, as acceptable, won’t create rules that actually moves towards the principle of ending the current hegemony but rather just seek to regulate it as is. If we add in open API’s and the increasing level of data mobility, portability and sharing whose “rules or principles” should be adopted?

How do your principles change when the underlying fabric of what is possible changes? The entire privacy framework, say in the US today, is based on early 1970’s reports written in the United States to address concerns over mass state databases that were proposed in the mid-late 1960’s and the growing data broker industry that was sending people catalogues out of the blue. It doesn’t take account for the world we live in now where “everyone” has a little computer in their pocket. Alas, IMHO, GDPR is not a lot better than rules with no truly human-based core principles.

The lobby of time

By example here is the 1973: The Code of Fair Information Practices This Code was the central contribution of the HEW (Health, Education, Welfare) Advisory Committee on Automated Data Systems. The Advisory Committee was established in 1972, and the report released in July. The simplicity and the power of the code have been eroded and water down so that the code is now ineffective. Would we be in a much better place if we had adopted such thinking at the time?

- There must be no personal data record-keeping systems whose very existence is secret.

- There must be a way for a person to find out what information about the person is in a record and how it is used.

- There must be a way for a person to prevent information about the person that was obtained for one purpose from being used or made available for other purposes without the person’s consent.

- There must be a way for a person to correct or amend a record of identifiable information about the person.

- Any organization creating, maintaining, using, or disseminating records of identifiable personal data must assure the reliability of the data for their intended use and must take precautions to prevent misuses of the data.

Conclusion

We have outdated “principles” driving rules in a digital-first world. This world is now dominated by companies setting norms and without reference to any widely agreed-upon values. The downside of big tech gaining so much power that they are actually seen by people-in-government as “equivalent to nation-states” is telling. We have small well-networked organizations attempting to make a dent in this. MyData, for example, has generated, from an engaged collaborative community, a set of ideals (principles) that provide a good starting point for a wider constructive discussion, but we need historians, anthropologists, ontologist, psychologist, data scientists and regular every day people who are the users to be able to close the loop between the rules we have, the risk frameworks we manage to and the principles that we should be aiming for.

How can we leverage innovative democratic deliberative processes like citizen’s jury’s that are used in some parts of Europe to close the loop between rules and principles around emerging technology?

Take Away

- How are we checking the rules we have are aligned to our principles?

- How are we checking our principles?

- Is our risk framework able to adapt to new principles and changes to rules?

- How do we test the rules that define and constrain create better outcomes?